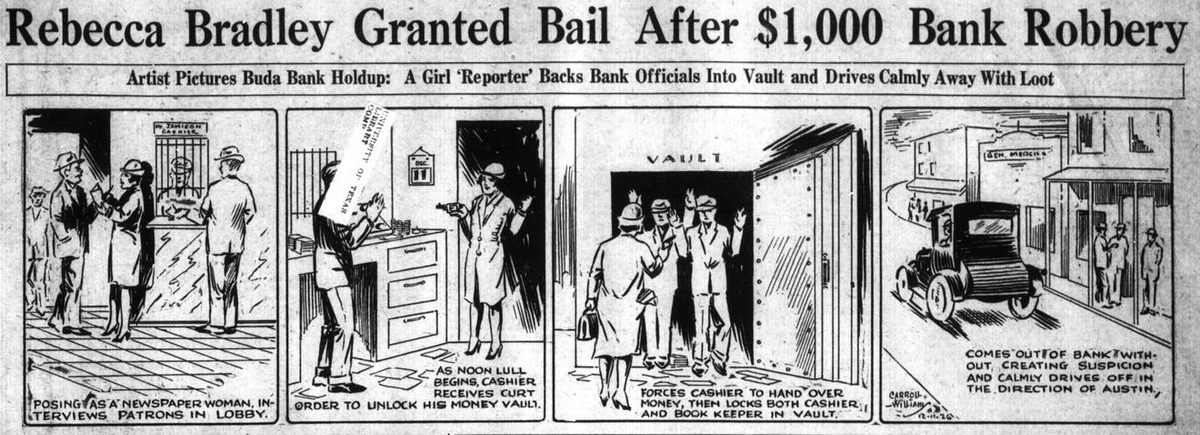

It’s a crisp Saturday morning on December 11, 1926, when a young woman walks into Farmers National Bank in the small town of Buda, about 15 miles south of Austin, Texas. Posing as a reporter for the Beaumont Enterprise, the five-foot-two woman with auburn hair and brown eyes moves confidently around the building, questioning residents about recent crop conditions. After gaining the trust of the two bank tellers, the woman slips behind the counter to use the typewriter.

One of the tellers makes a deposit in the safe, and, as he turns around, he finds himself face to face with a cocked .32 automatic pistol, held by the fake journalist, 21-year-old Rebecca Bradley. After ushering the two bank employees into the vault, she pauses to ask if they will have enough air to survive for 30 minutes before locking them in. Then, she takes off with $1,000—the equivalent of over $17,000 today—in five-dollar bills, and hightails it back to Austin.

Despite the crime, the bank tellers described her as “quite courteous,” according to Michelle Haas, chairman of Texas History Trust, a non-profit focused on fact-based storytelling of the state’s history.

Within hours of the robbery, the Austin-American Statesman ran a story titled “Flapper, 17, Takes $2,000 in Currency at Gun Point.” The headline is riddled with inaccuracies, but gives Bradley her catchy moniker. The real details may never be fully known, but historians over the years have relied on news articles and court records to piece together the story of Rebecca Bradley, the Flapper Bandit.

Despite her nickname, Bradley wasn’t known for wearing rouge or gallivanting around town, or really participating in anything risqué at all, Haas says. She was studious, held several jobs, and was working toward her graduate degree in American history at the University of Texas at Austin. In 1924 and 1925, she even served as vice president of the local chapter of the Present Day Club, an organization of women who were pro-prohibition and—ironically—met to discuss solutions for the growing crime wave of the 1920s. After her arrest, many of her peers defended her, stating that she “simply wouldn’t do a thing like that,” reported the Fort Worth Record-Telegram in 1926.

Bradley was just one of many so-called “flapper bandits” who took over American headlines—from New York to Texas—throughout the 1920s. Like Bradley, most of them were not really flappers, but regular women who got caught up in crime and were cast as sexy but scary outlaws in the media. “It is an entirely manufactured thing,” says Stephen Duncombe, who co-authored a book on a notorious New York Bobbed Haired Bandit—another name for a flapper bandit that nods to the new, short hairstyles women were wearing at the time. “Were there female criminals? Definitely. Were there female criminals who were cutting their hair in bobs? Of course, because it was the Twenties. Were they flapper bandits? No. That’s just a media construction.”

The Roaring Twenties were a time of big transitions. Women—white women, at least—were given the right to vote, began to join the workforce, and gained independence. Some women were getting short haircuts, wearing flashy dresses, and participating in so-called promiscuous behavior—and that scared people. “The Bobbed Haired Bandits became lightning rods for all of these concerns,” says Duncombe, a professor of media and culture at New York University. “They represented anxieties about women and their independence.”

For example, Bradley drove her own car, which was still uncommon for women at the time. And after the robbery, that car would be essential to her escape.

Bradley decided to take the backroads home to Austin, where her car got stuck in the mud. She hailed down a milkman named Frank who pulled her out and sent her on her way, Haas says. Once back in Austin, Bradley dropped the car off to be cleaned and walked to the apartment she shared with her mother. Here, she put the gun and $910 in an empty chocolate box, which she then mailed to her university address, in an effort to hide the evidence.

Thinking everything was taken care of, that afternoon, she headed back to the shop to pick up her car. When she arrived, the police were there to greet her, handcuffs first. It turned out that a Buda resident recorded her license plate, sealing her fate.

“I have a whole lot to live down, but not as much as those men back there who let a little girl hold them up with an empty gun,” Bradley proudly said on her ride to the Hays County Jail in Buda, according to Sheriff George M. Allen’s testimony in the Austin-American Statesman.

The morning after Bradley’s arrest, her employer bailed her out. But her freedom didn’t last long. Bradley was arrested again on December 15th for arson charges in connection with a failed robbery attempt in Round Rock, Texas, 30 miles away from Buda. There, she pulled a similar ploy, pretending to be a working journalist, the very day before the Buda robbery. Thinking it would draw the tellers from the bank, she lit a vacant home across the street on fire. It didn’t work. Later, witnesses—including the store owner who sold her the kerosene and matches—identified Bradley as the arsonist.

People still couldn’t connect the reputation of the respectable young woman with her actions. Bradley’s explanation, according to her own written testimony—pieced together from news reports—was desperation, Haas says. “Finally, she just said, ‘Screw it,’” Haas says. “I’m going to quit everything, and I’m going to right this wrong.”

That testimony outlined the series of events that drove Bradley to her crime. “It wasn’t especially flattering of herself,” Haas says. A few years before the robbery, Bradley took in her motherm who had recently been laid off. Keeping house, going to school and work, and caring for an aging parent were all too much, she wrote. Three years before the robbery, she started to fall behind on her work at the Texas Historical Association, including the task of collecting dues from members. To hide the missing money, she started paying it off from her own bank account, putting herself into debt.

Eventually, it was impossible to hide. Bradley wrote her boss a letter admitting to everything she’d done, and promising she could pay him back the $2,000 she now owed. In her mind, the only way to get the money would be robbery, Haas says.

Citing this rather candid and unapologetic confession, Bradley’s defense team claimed she must have been out of her mind. Calling on several medical examiners, the lawyers argued the young woman had dementia praecox, now known as schizophrenia, leading her to think she was justified in robbing those banks. The prosecutor said the disease “is what someone has when he is caught,” Haas says.

Though Bradley was living in a time of change, old sentiments around women and their mental fragility still stuck, and may have worked in Bradley’s favor. One of the judges believed “she was so pretty that there’s no way she could be a criminal,” and blamed the crimes on her menstrual cycle, says Linda Coker, chair of the Hays County Historical Commission, presiding over Buda.

Whether a convenient scapegoat or the truth, the plea seemed to work. Despite being cast as mentally unstable in the courtroom, people began to fawn over the Flapper Bandit. She was just innocent and pretty enough for the more conservative crowd, while also being unruly enough—known to make fun of male reporters and dodge photographers—to intrigue the counterculture followers of the time. “It’s interesting how she became the darling of the media … she was pretty, and she knew how to play them,” Haas says. While it’s hard to say who Bradley really was—“I can’t know her heart or mind”—the way she was portrayed by the press may have had a lot to do with the outcome of her case, Haas suspects.

For seven years after the robbery, Bradley endured several hung trials, only a brief time in jail, and a retrial that ultimately concluded with her freedom. While the district attorney stated that the case would stay on the docket, nothing came of it. In 1933, the day before Bradley was to give birth to her first child, the state officially cleared her of all charges. With the salacious title of the Flapper Bandit behind her, Bradley was finally free to focus on the next chapter of her life.

With her legal troubles behind her, she did her best to bury her past, going on to lead a quiet life as a wife and mother. While Bradley may have never been the flapper girl the media projected her to be, she stood as a symbol of the conflicting times, representing a larger fear of women’s independence. “Had it been a decade later or earlier,” Duncombe says, “she would have just been another woman committing a crime.”