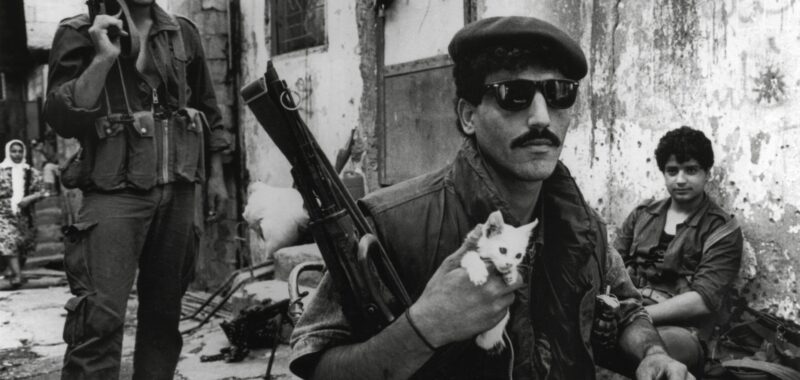

In 1988, photojournalist and photo editor Aline Manoukian captured an image of a Palestinian militiaman holding a white kitten in Lebanon’s Burj Al Barajneh refugee camp. That photo would go on to circulate for decades, recently appearing across social media platforms in doctored forms, including as a colorized poster.

When I went on a research trip to Lebanon in 2017 for my new novel, The Burning Heart of the World, I met Manoukian for the first time. We both come from Armenian families, and mutual Armenian friends put us in touch; that’s the way things often work in our community of diasporic artists, writers, and academics. We went out for dinner in Hamra and then moved to the Abu Elie Bar to continue our conversation. Manoukian, who is a captivating storyteller with a fiercely independent spirit, reflected on her experiences as a child, an adolescent, and then as a young woman photojournalist during the Lebanese Civil War, which led to her time working as the Reuters bureau chief for Lebanon and Syria. In a recent Zoom conversation, Manoukian spoke with me from her home in Nicosia, Cyprus, about the formative influences of her early career, as well as about how she manages the trauma inherent in documenting conflict 50 years after the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Hyperallergic: What set you on the road to becoming a photographer?

Aline Manoukian: My biggest influence was my sister, the painter Seta Manoukian. Seta has been my sister, my mother, and my best friend. Everything I’ve done, I owe to Seta because she’s my role model of an independent woman. It’s because of her that I went toward photography. Seta had lots of art and photography books that she brought back from England and Italy. I spent my childhood on a rug in the dining room studying these books. It opened my eyes to visual art, to composition, to light.

H: Who is your favorite photographer?

AM: Mario Giacomelli was the first one who opened my eyes to the possibilities of photography. I came upon his book for the first time in the library when I was a student at Pierce College in Los Angeles. There was a photograph of monks dancing in the snow. There were a series of them, but one really struck me. I knew that I had to have that photograph. I looked around to make sure no one saw me, and I tore out that page and hung it on my wall. I committed this crime of tearing a page from the book.

H: Do you feel guilty?

AM: I still feel guilty because I deprived other people of seeing that picture. It was selfish, but I had to have it. It changed my life.

H: What was the first camera you owned?

AM: The first camera that I used professionally was a Nikon FM2 that Seta bought me. Unfortunately, somebody stole the lens. I had a call from AP that same week assigning me to go to South Lebanon and I didn’t tell them that I had a camera without a lens. I went anyway because I knew there would be other photographers there. I didn’t tell them that I was there on assignment without a lens. I pretended that I was working normally, and I would ask photographers to lend me their lenses if they were not using them. And that’s how I completed my assignment for AP.

H: When did you start working for Reuters?

AM: At the end of ’83, I started at the Daily Star. Then UPI hired me as a stringer. In 1984 I ended up at Reuters. I eventually became their bureau chief.

H: You were 19 years old when you started?

AM: 19 at the Daily Star, 20 at Reuters.

H: And had you graduated from Pierce College?

AM: I didn’t graduate. There was the Israeli invasion in Lebanon at that time, so my father couldn’t send any funds to pay tuition. Also, I wasn’t too interested in studying. I started running around in the LA punk scene. My sister and brother who were in LA thought this was too dangerous. They decided to send me back to Beirut.

H: Lebanon was less dangerous?

AM: For my own security, they sent me to a country at war. My sister introduced me to this Lebanese photographer who was supposed to show me how to work in the street. His first lesson in photojournalism was a story. He said, “There was a child sitting in the middle of the ruins of a house that had just been bombarded. I took a picture of the child in the ruins, but it wasn’t a good picture. So, I started shaking him to make him cry and he wouldn’t. I shook him some more, and then his mother came over and said, ‘What are you doing to my child?’ I asked her, ‘Do you want your child to be in the newspaper?’ And she said, ‘Yes.’ I said, ‘Then make him cry.’ She slapped him, and the child cried. I took the picture, and this was a good picture.”

H: That’s horrifying.

AM: I thought it was bullshit. I went out on my own and started snapping pictures in the streets. One day, a school friend who was a Red Cross ambulance driver asked if I wanted to go with them to deliver bread. I went in the ambulance to Ras al Naba’a. I didn’t think I was doing anything exceptional, but it turned out the area was besieged by snipers, and no one was able to go in or out except the Red Cross. In the end I had done an exclusive, and when I brought the pictures to the Daily Star, they used them, and they hired me. So, I say my career as a war photographer started by accident. I mean, I wasn’t aware of what I was doing. But even though one man tried to lead me in the wrong direction, there was another who believed in me since day one. I owe my career to the late Claude Salhani of UPI who defended the undefendable. [I was] a very young woman photojournalist in the middle of a man’s world.

H: Do you have a favorite among your photographs?

AM: The picture of the militiaman with the cat. It’s my iconic picture.

H: Does being famous for that image bother you?

AM: Absolutely not. That picture has a life of its own. Whether I like it or not, that is my favorite because everybody likes it. The majority wins.

H: Do you still think of yourself as a practicing photographer?

AM: No, not today.

H: Did you stop at a certain point, or was it gradual?

AM: It was gradual. I still take pictures, but I don’t walk around with a camera anymore.

H: What is the best part about being a photo editor?

AM: It’s the responsibility of making or breaking it for a photographer. If you edit their pictures with care and understanding, you can help them be successful. Pictures go through many stages before they reach the viewer. The editor is a huge part of the process. Because the photographer cannot step back to be able to judge his or her own picture, especially when it’s a series. As an editor, you’re judging the pictures for how newsworthy they are, and how aesthetically balanced. Later you see that the pictures you edited have won prizes. It’s gratifying, but nobody thinks about the editor, not even the photographer.

H: I was recently reading Lebanese writer and painter Etel Adnan’s 1995 essay about exile. Do you feel like an exile yourself?

AM: When I was born and raised in Lebanon, there was no question I was Lebanese. Then I have lived so much abroad. I lived three years in Los Angeles, 26 years in France. Now I’m in Cyprus. I was cut off from Lebanon for a long time, and recently, I asked myself the question, “Am I still Lebanese?” My sister used to say, “You don’t feel Lebanese if you don’t have a village.” Because everyone in Lebanon has a village they come from. Can you feel like you belong to the country if you don’t have a village? And for me, I’ve been away from my village for so long that I wonder if going to Lebanon is returning home. I don’t know where I belong. Roots end up drying out if they’re not watered.

H: In a 2018 video interview with Fighters for Peace, you said that during the Civil War, you learned that people who were normal and kind could turn into violent monsters overnight.

AM: Mostly because of circumstances.

H: You also said that you never wished to belong to a group.

AM: Groups fascinate me, and I understand their necessity. But I wouldn’t want to belong to a group because I’m in perpetual doubt. If I criticize a group that I’m in, I will be called a traitor. I can never be called a traitor because I was never a part of a group.

H: In another video interview with Cinejam, you talked about the smell of war. You said that the problem with photos is that you see only the images, not the smells and sounds, as if they reside in the body. Do you think these residues ever dissipate? Or are they permanent? And if they are perennial, how do you manage them?

AM: Denial. I’m in constant denial. I have a tendency to sweep everything under the carpet.

H: The traumatic experiences embed themselves in the body, so when another round of violence starts, those wounds open again.

AM: That’s what the Gaza photos do to me. They revived everything and you feel when these things are revived, you feel something physical, as if your cells are rotting. That’s how I feel with the pictures of Gaza. Sometimes I just burst into tears. But then I go back to denial mode to survive. It’s a survival mechanism. It’s the only method I know.